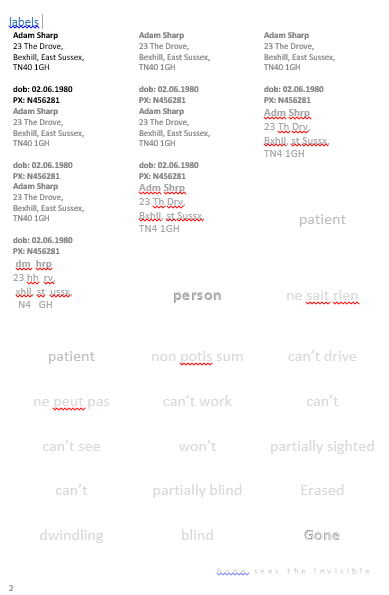

Person. This story is about Adam, a person.

Patient. In some people’s eyes, Adam is also a patient. These people are part of the medical establishment. To them, he is patient, has to be other, the object of their care. Without this otherification, he is dangerous. Sometimes Adam feels like he is no longer a person. Is he a number, an object?

Practitioner. Optometrist, General Practitioner, Registrar, Consultant Neurosurgeon, Health Care Assistant (HCA), Nurse, Porter, Theatre Nurse, Technician, Ear, Nose and Throat (ENT) Specialist, Consultant Anaesthetist, Consultant Neurosurgeon (again), Registrar (again), Senior Registrar, Have I lost you yet? Adam feels lost amongst this barrage of qualifications, acronyms and hierarchies. Name badges make little difference when you can’t see. Nurse, Nurse Practitioner, Health Care Assistant (HCA), Porter, Consultant Neurosurgeon (again), Registrar (again), Senior Registrar (again), HCA, Nurse, Occupational therapist, physiotherapist, psychiatrist, counsellor, general practitioner

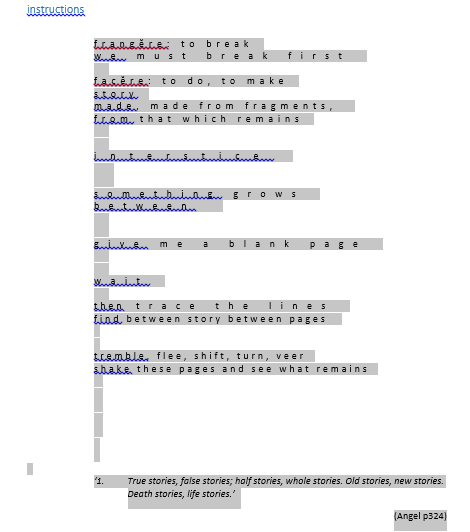

Paper. This is a term paper, which I present to you for marking. Within this paper is a fictional paper written by a fictional doctor for a fantastical version of a journal for doctors, the British Medical Journal, and outwith this paper is a paper on blindness that would not stay unwritten. Each sheet you hold is paper, pulped wood, smeared with petrochemicals. Inkjet ink will smear with tears. Papers determine one’s identity: in this paper you may find out more about Adam, about the relationship between person and patient, between patients and practitioners, about me, the author, perhaps about yourself too.

Record. This paper is a record, but what is it recording? A record is a testimony: I write this on behalf of those who cannot write, speak, see. Memory, statement, report, in black on white. A written account of event(s). An achievement. Nothing in here is off the record, but it seeps out from the boundaries of the record; what I have read sprawls across this record, bleeding print, ideas that haemorrhage unstopped

Story. Story, first, was history. Now, story is, ‘a narrative of fictitious events, designed for entertainment’. Beyond definition, story is elusive. It dances between fact and fiction, fragments and the whole. It lives in the space between the sheets of paper, not just in the inked words on each page. It finds a space in your mind: story is nothing without mindspace. Story is not, if it is not read, not told. Story is personal, of a person, for people. See, speak, write, create a story, find a (happy) ending.

Tumour. There’s a tumour in Adam’s brain. As a sneak preview, I’ll let you know it is a pituitary adenoma. Does that mean much to you? Never mind. A few millimetres of errant tissue in Adam’s brain changes his behaviour, his choices, his life, his story. Meaning collapses for him. Mind you, when the story starts, he doesn’t yet know that he had a brain tumour. Bear that in mind.

See. Seeing: we see without thinking, we ‘look, behold; observe, perceive, understand; experience, visit, inspect’. I see: I follow what you are saying. I see: I have (a) vision. Also, See, ‘throne of a bishop, archbishop, or pope’ from Latin sedem ‘seat, throne, abode, temple,’ related to sedere ‘to sit’. I do not see, I am unseated.

Blind. Lacking sight? Unable to see? Blindness is seldom total lack of sight: most blind people have some residual vision. For them, life depends on exploring what is left. Think of blindness as part-sight, ‘now we see through a glass darkly’. The original sense of blind comes not from ‘sightless’ but ‘confused,’ underlying phrases like blind alley.

Sight. A thing seen, esp. of a striking or remarkable nature; a spectacle, a vision. The apocalypse. Something which calls forth contemptuous, horrified, or amused glances; a shocking, repulsive, or ridiculous spectacle. A show or display. Aspect, appearance, look. The perception or apprehension of something by means of the eyes; the presentation of a thing to the sense of vision. A view, a glimpse. Hold all these aspects of sight in your mind’s eye.

Loss. Something is missing, disappearing. At first imperceptibly, sight vanishes. Adam becomes aware of this slowly. Something in this eludes me, I cannot address it adequately in 6000 words. Practitioners lose perspective. Adam loses his personhood, loses half his field of vision, loses his …

… Pouvoir. (French) v. to be able to, can, may, might, n. power. From the Latin, potis sum, to be master of. Command, agency. Adam loses his ‘pouvoir’. Some is snatched from him, physiologically, some is taken by a system that disempowers him. Impuissant, he cannot see, so he cannot [………..].

… Savoir. (French) v. to know, to see, to be aware, to realise. n. knowledge, learning scholarship. from Latin sapere, (nominative sapiens), from PIE root *sep- (1) “to taste, perceive”. Homo sapiens – to be human? Knowledge, empathy, understanding all are needed to be a medical practitioner. Henry Marsh writes in Do No Harm, the voice of the practitioner for the purposes of this paper, ‘illnesses happen to patients, not to doctors.’ (p215) Knowledge, savoir, has a protective function. Adam is unseated, unsettled, uncertain, sans savoir.