Women have always done it, unrecognised, hidden. And even once allowed, we deny it, because being allowed in itself takes something away. Who offers the permit, and do I want it anyway? I may continue in secret. No-one will know, either way.

it’s warm and dark red and the woosh-thump-woosh-thump’s always there, and I’m on my own/never alone safe warm nourished part of you and that’s all I want and ever need

jerked screaming, fighting every push and brutal squeeze, too bright, too hard, can’t go back, let me back let me back, let me in … skin touch soft warm fill me keep me safe together

I have a room where I go and close the door so no-one can reach me. It seems like I’ve had it forever, but there must have been a first time that I discovered it. Everything has a beginning …

rewind until I can hear her screaming at me, until she’s grasping my wrist, and I’ve done something wrong and I don’t know what still don’t know, and her breath smells and I look up into her eyes and know that I’ll never be right so I need to vanish. I stand still, her bone-witch fingers surrounding my wrist, and as she shouts down at me I can’t move. Tell me it will be okay, but there’s no-one else but me and her and brick by brightly coloured brick I build until I vanish. I’m gone where she can’t touch me anymore and that’s when I find my room.

Ten years on, my room has materialised. I learned to read and a door opened into somewhere I never knew existed. I can retreat until I don’t hear the screaming anymore. And when I’m all wrong, don’t fit it, don’t get the joke, can’t play with us, my room’s still there, where I can’t be touched. John Peel’s on the radio, though, and I believe that somewhere there’s a way out.

In time, I discover that I was right, and I pretend the room’s gone. I watch as the sky fades, blue, green gold, to darkness, setting sun, silhouetted trees and chimneys. I’m in the attic, real room of my own. Mismatch thrift shop furniture and peeling wallpaper spell freedom. Rent paid, I can enter and leave when I want. I lie on the worn grey carpet and reward myself for each page I write, each sunset I paint.

At night we drink and smoke and dance and the music’s louder than my heartbeat, until the sky lightens from navy to turquoise again. Milk fresh on the doorstep, we stumble back indoors. And later when I’m heaving the night into the toilet, my t-shirt clings against my skin, and I go to my room, but I’m not telling anyone. I creep in, furtive, would never tell, never share, can’t admit that the room’s still there.

I’m spent, another night, red wine in jugs you can’t tell how much you drink and we were laughing so hard my throat’s sore and my ears still hear the music and now it’s all stopped, and I’m chilled, skin clammy, but inside my head is quiet and I’m not dangling on the edge of madness, won’t see a counsellor, see her, won’t see her again.

Another ten. I’d get up if I could but the gap in my symphysis pubis is too large, and the baby stretches my belly, I’m seventeen stone at my biggest, and my mind has slowed like my steps. The sun shines in, cats rolling on the golden carpet. My world has titrated down to one room, can’t diminish any further, but it’s not the room I was thinking of.

I’m never alone, and it’s eating me and I want to be one, own, me, gone, and the drugs take the edge off and gradually I claw back a tiny place that’s my room. I can sit still, feed the baby, watch birds in the garden and think. There’s something new, though, and it glows green as I realise I’m not allowed to be alone.

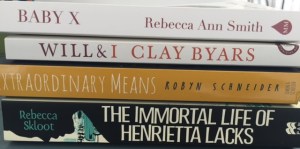

Maybe the end should have been when I delivered the baby, but I’ve found that’s not an end. And now, behind a barrier of books, I am rebuilding my room, stealing back moments to write. My desk is tall, broad, blue-stained, grain of the wood still visible, family photos backdrop my thoughts. Does time need to be scarce so I write every word?

Mum, mum, I need a drink, did you get more eggs, can you wipe my bottom, can you drop the car at the garage, what’s for tea, I’m going to be late, can you help me with my homework, you never told me it was parents’ evening, where’s my socks, I need a lift, is there more cake, he’s got all the socks, that’s mine, I want it, it’s not fair, I want, it’s not fair, I want, I want, I want …