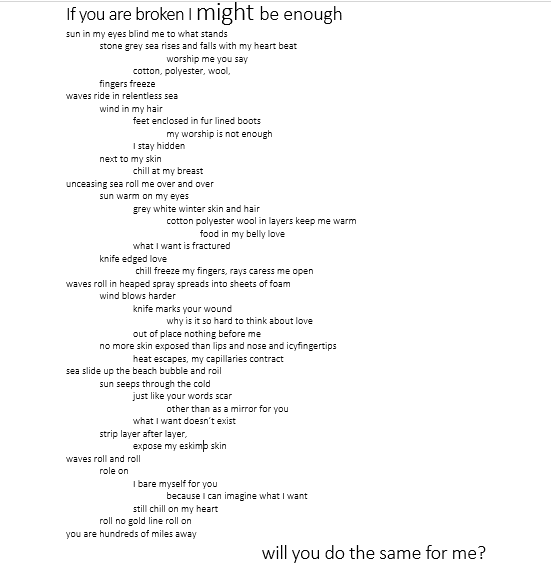

this term we have been exposing unwritten rules about writing.

Do you always start sentences with a capital?

why? because you were told to? what happens if you don’t?

writing without rules, outside rules, with new rules, your own rules, any sort of experimental writing, is scary, exposing, liberating.

try to write with new rules, with the rules that you devise yourself, with

my rules,

his rules,

her rules.

when you write like this Do you find a new you?

have you got a pen? do you need one to take part in this class? do you have to write with pen on paper, black on white? black marks on a screen? what happens if you write in white on white?

does your writing need to be understood?

Take away the rules of writing, and what are you left with? There’s nothing scarier to a writer than a totally blank page: at the same time that page is full of potential, the perfect object of desire.

Give me space to write and I could write anything.

So, here goes. I’m giving you a space to write. Space with new walls, new rules.

Go to the supermarket, the café, the corner store. Hang out at the back, try not to look too suspicious. Eye up everything they have chucked out until you find the cardboard boxes. Look for the biggest box you can find. If you live near Ikea, all the better. Pick a box, big enough to fit a body in. Take it home.

Set up your box. Use tape to reassemble it if it has been flattened. Switch off your phone.

Take your box, and find it a place. This might be the bathroom, perfect if it has no windows. What about the basement, the attic?

My basement is concrete lined and dark.

Find a marginal space, somewhere you won’t be disturbed. If there are windows, pull the curtains. Lock the door. If there is a light, put it out. Do you need clothes? If not, disrobe. Pick up your pen: I did say that you’d need a pen, didn’t I. Choose the colour of your ink.

My ink is white.

Climb into your box, seal yourself inside, sit there, legs furled, pen in hand. Eyes shut.

Feel the card against you, warm card, warm skin. Do you want to move, wriggle, shuffle? Adjust your position until you can be still, then sit again until the bones of your pelvis burn and your spine fuses.

Listen. What can you hear in your box? Water flowing through pipes? The rustle that might be mice? The rub as you breathe in and out? The whoosh of blood in your ears. Impulses racing down nerves, the message each sound sends to your brain? Listen until you can hear your irises dilate.

Open your mouth. What is on your tongue? Is the air stale, metallic? Can you taste the last meal you ate, lingering garlic? Do you thirst? Salivate, and taste yourself.

Inhale. Smell the room around you, your own scent, that of the box. Stay there, stay with that, how long do you need to stay there before it changes? When do you end up immersed in the scent of your own excreta?

Now, open your eyes. What can you see? Is it dark in your box? It’s not, not really, not if you have sat there long enough for your irises to dilate, your rods to adapt, for every cell in your retina to scream for stimulation. Track the lines of light where the box is made, the outside world seeping in through cracks and corners, follow them round and round, up and down, trace them with your gaze until your head spins and you no longer know which way is up.

Now write.

Write your heart beat, write your enclosure, write out, write infinity. Write secrets, write blindness, write what you know and what you don’t know, never knew, will never ever know again. Write on the walls of your box until they are covered, and when you have covered the walls write on your own skin, until there is no boundary between you and your box and your pen has run out of ink. And if you need to write more, you must write in your own blood.

When you have written, burst open your body, your box, cardboard sprawl on carpet, on concrete.

Flatten your box. Expose your words, let light in and see the true colour of your ink.

Lie on your box and be your words. Ride them, wavewords, ride them, sightless horses, ride them ecstatic until they cast you back on the shore.

Spent.

Bibliography

Helene Cixous The Laugh of the Medusa (1975) in The Routledge Language and Cultural Theory Reader, 2000

Helene Cixous Writing Blind, in Stigmata, Routledge 1988

CA Conrad A Beautiful Marsupial Afternoon

It’s term paper time. Experimental writing term paper time. Whatever comes up next on the blog should perhaps come with a warning. It’s written for a very small audience: people who are interested in sight and blindness along with experimental writing and the avant garde. I suspect I may be the only person in the centre of this Venn diagram … but I’ve been bitten hard by this one, it’s obsessing me, and I have so much more written than will fit in the term paper, and it’s all going to end up here …

It’s term paper time. Experimental writing term paper time. Whatever comes up next on the blog should perhaps come with a warning. It’s written for a very small audience: people who are interested in sight and blindness along with experimental writing and the avant garde. I suspect I may be the only person in the centre of this Venn diagram … but I’ve been bitten hard by this one, it’s obsessing me, and I have so much more written than will fit in the term paper, and it’s all going to end up here …